Wadada Leo Smith : The OFN Interview [part 1]

by Matthew Sumera

April 2005

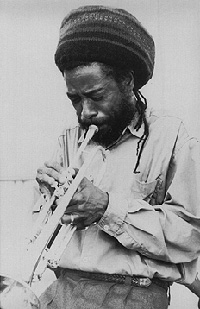

[part 1 / part 2]  Wadada Leo Smith remains a pivotal figure within contemporary creative music. As a player, composer/improviser, educator, and musical theorist, Smith’s contributions touch upon the history and future of jazz in all its incarnations. His current collaborations—from his work with Henry Kaiser and Yo! Miles, to his Golden Quartet, to guest spots with Spring Heel Jack and his association with John Zorn and Tzadik—hint at the breadth of musical influence and inner commitment that continue to drive Smith’s explorations into the meaning of sound. Wadada Leo Smith remains a pivotal figure within contemporary creative music. As a player, composer/improviser, educator, and musical theorist, Smith’s contributions touch upon the history and future of jazz in all its incarnations. His current collaborations—from his work with Henry Kaiser and Yo! Miles, to his Golden Quartet, to guest spots with Spring Heel Jack and his association with John Zorn and Tzadik—hint at the breadth of musical influence and inner commitment that continue to drive Smith’s explorations into the meaning of sound. Recently OFN’s Matthew Sumera had the distinct privilege of talking with Smith at length as he was preparing for a Spring European tour (tour information available from Cuneiform Records at http://www.cuneiformrecords.com/tours.html). His passion, dedication, love, and endless interest in music and musical worlds, and the significance of music in our lives and hearts, pours forth in every sentence and phrase he utters. Generous with his time and ideas, Smith is a wellspring of musical wisdom, a master of both thought and execution. If the term “tone scientist” ever meant anything, surely it can be applied to Smith and his unending inquiry into the nature and importance of music to our world and our very survival. Smith lives life as music and music as life. One need only talk with him, even for a short while, to quickly realize that the two are inextricably linked, neither being able to survive in isolation from the other. This is the essence behind all that Smith does and perhaps his greatest gift to the rest of us. He challenges us to see the truth in one simple yet profound maxim: Life is song. Due to the length of the conversation, OFN will present the entire, unedited interview in two parts. I’m interested in why you first chose to play the trumpet? You see, I really wanted to play drums when the music came to my school, and I had no idea about playing trumpet because drums is kind of visible and most people, you know when they’re young, they kind of see drums as the most exciting instrument. Normally everybody can beat something, you know. And so I got in line, and when I got up to the desk they said, “What you want to play?” and I said, “Drums.” And they said, “We don’t have anymore drums. Take this.” And he gave me a mellophone. And the mellophone I did not like because it doesn’t play principal parts, and at that time I didn’t really know that, I just didn’t really like the way it looked, and the shape, and how it was feeling, you know. So I guess the teacher kept me on that for a little bit, a mean maybe, what, a month or six weeks or something like that. And then one day he was so frustrated with me and another guy whose name was Henry that he said, “Look, you go over there and send Henry over here.” And in Henry’s room he had the trumpet and in my room I had the mellophone. So he just, you know, just out of sheer frustration switched us. And it was the best for all three of us. Henry became the best French horn player in my school and I became the best trumpet player. And we also made a good band together with this director. And when did you decide that you were going to stick with the trumpet and stick with music? When I was 13. Because I started playing when I was twelve and, you know, I did a show after that on my birthday. I started playing for people three weeks after that. So when you started playing, what initially drew you to the music and are those the same things that continue to draw you to it today? Well, I guess underneath there was a great desire, or feeling, or passion, to be involved with art or music. But a closer model was my stepfather, by the name of Alex Wallace. He was the musician in the family. He played the guitar and he sang and played in blues bands and knew all the blues music and musicians of that time. I would say that was the everyday model that I had of what music was meant to be, as an example of what an artist should be. So I think that was the primer to find out that I cared about art... and I’m speaking of music in broad terms as art. And is that what continues to drive you today? Well, what continues to drive me today is what’s inside of me that calls for inquiry into the nature of music, period. And the nature of really how one deals with art objects and how those art objects are really institutions that express profound ideas about how this person, or any other person, views creation. It has something to do with that. How do you approach your music both as an improviser and as a composer to address those issues and is there a difference in that inquiry if you’re improvising or if you’re composing? Well, let me answer that question this way: There’s a big difference if one selects either/or as a medium to make that journey. But if one selects a new dimension which is the composer/performer/improviser, if you select those three categories, then the inquiry serves for all three at once. But if I just choose, let’s say, to just be a composer, my inquiry would be very limited. And the same would be if I chose to just be an improviser. It would be very limited. So the composer/improviser/performer... Must be the commitment. And it’s also one of the most perfect dimensions for one to make this inquiry because we are speaking of a person who composes music using systems and concepts and languages, and we’re talking about a person who creates an improvisation using systems, concepts, and languages and we’re talking about an individual who plays other music, that is in the performer context, a person who plays other people’s music that has those elements in it. I’m interested in how you approach teaching and perhaps why you chose that route and what you get out of it? I have a class that I’ve taught for the last ten years, it’s called “Composition and Improvisation Analysis”. It’s a two-semester course, and one proceeds the other one. And if you walk into either one of them, you couldn’t tell the difference between them because, simply, I use composition and improvisation analysis in both semesters kind of simultaneously. So that if a kid doesn’t get it that semester, he gets it the next semester. But my approach for teaching—well, the reason I teach is because I think that that is one of the ways that, in regards to the inquiry, opens the questions for how to look and where to begin to look. Teaching brings out of you your deeper commitments toward humanity as opposed to one who just cares about themselves. It allows one to explore opening up other minds how to see. You see because teaching is that. That’s what teaching is. It’s showing how to see. To teach ideas and concepts and systems and languages in themselves don’t show you anything. They don’t teach anything. But showing how to see, then the person has a springboard in which you can look at all these things and then begin to inquire into the depth, the deeper depth, of what they’re about. And using skills I give them how to see, that is the method that I use for teaching and I feel that’s the most important—the most important component in teaching is to show them how to make this gain, this search. And do you feel that you derive something back as far as your own inquiry from working with students? I do. I have to do the research. To start out with, if I say that I’m going to look at six major compositions by Miles Davis or John Coltrane, or let’s say Bob Marley, or just Charles Ives, I have to do the research and come up with ideas about that music, and also I have to find something there to show them that they’ve never been shown before. Because if I show them what they’ve been shown before they become accustomed, like people become accustomed to sunglasses think that it’s just an ordinary sunrise, that is that it rises up and it’s got light. But that’s not true. You know, the sun comes up from different spots on different times of the year, and it does something different for the environment on each of those occasions. That’s very interesting. It sort of reminds me of certain poets talking about the role of poetry is to make people re-conceive of words, you know, get back to the original naming. So instead of saying “that’s a dog”, you actually define it in a way that the multiplicity of meaning is inherent within that definition... But you see, the artist’s responsibility is for the observer, or participant, it is to really open up the value of how you see the same occurrence over and over and to see it with new vitality and vigor. And it’s not only that you’re not seeing the same thing, but the art is there to aware those participants that that something that they’re hearing is not only different but that artistry crystallizes the mind and the heart so that they can see those distinguished differences that makes the day extraordinarily different than it was if they don’t see that. If they don’t see that, they become bored and so “it’s just the same day”, and “nothing is new under the sun” and all these kinds of things, when in fact they’re making a great error about the environment of which they should be more careful observers of than they are expressing at that time. From the audience point of view then, is that understood logically, is that understood emotionally? How do you think that people get to understand that message? Well, you know, like professional people should dig a little bit deeper and the meaning that they would gather from it is based off of their experience. And the people that we call the ordinary—which is not quite ordinary, they’re really extraordinary—is that they also will get something based off of their experience. In other words, to use another metaphor, if you’ve got a big dipper and a small dipper and a long dipper and a short dipper and you dip it into a well, the results are going to be different. But everybody’s dipping into the well. If the dipper is small and you can quench your thirst with a small dip, then that’s fine. But if it takes more than one dipper, than you have to search with the long one. So ordinary listeners can gain this same information—because really to understand anything is to place it within the context of your own intelligence and the way that your own heartbeat motivates you. Because the center of the body is not really the mind, it is the heart. You know, it’s not the brain, it’s the heart. And I don’t mean that life is ended when the heart stops, and this and that, I mean that human beings make their deepest connections and awareness from their heart. And consciousness is transformed from the heart and not the mind. So if you’re saying that as a listener for me to understand something I need to put it in my own context, what value is there in understanding perhaps the context in which it was created? There’s great value in that because it involves analysis, you see, in trying to analyze it. And what it does is, when one analyzes a piece of music you’re looking at how it was put together, you’re looking at motivations, why it was put together, and you’re looking at what does it do once it’s put together, you see. And that inquiry is really set up to take us back to, intuitively speaking, back to the choices made by the artist that put that art object together or created it. And their choices can teach us a lot about ourselves. You see, analysis plays a strange role. What it does is open us up enough to realize something about ourselves in that process. And ordinary listeners, people that participate in listening, and you know, music lovers and art lovers and people like that, they arrive at some of the same conclusions if in fact they are reflective. You see, if they just do a little bit of reflecting they come to the same kind of conclusions. But the conclusion is, they don’t see the mind field in which the analyst sees, in doing the job, but they do see the same result that comes out of it. When you’re talking about—and I’m interested in this in particular in relation to your Yo Miles! project—when you’re talking about analyzing at the time of the creation the structure and the motivation that, say, Miles Davis had during that time, and as important you had mentioned, what that sets in motion, perhaps politically and culturally, the impacts of that... how do you then go back, once you understand that? And at what point do you decide that you want to engage in doing those kinds of projects? Well, actually I decided instantly to engage with Henry to do this project. He was at a solo concert I did, and he asked me if I was interested. He told me that he was thinking about doing this concept, and I said, “Yeah. We could do it.” But the other side of the coin is that knowing what I know about Miles’ music, I place it in context. I mean, over the years, over the last 20 years I’ve been teaching, I place it in a context, which gives me a good advantage of seeing how to do it and how to think about it, you know. For example, look at Miles to understand the complexity and multiplicity of other musics, of the very dance music, that he created. If you go back to the African drum orchestra, the West African drum orchestra, it is the perfect model of how to begin to appreciate the multi-layers of complexity that Miles’ ensembles are demonstrating. And once you start looking at that, you go below the layers and try to find out, well what does he use, what kind of language inside of this unity does he use to explore his musical resources through? And I came up with the idea that most of his compositions/improvisations were formulas for music. You know, formulas for pieces. Like for example, some pieces would have the same bass line as other pieces, but the material on top of it and that’s associated around it, be it horizontally or vertically, are entirely different. And that was one practice he used. And another practice is that he also, and when you look at his pieces and go through note values and note differences, you’ll end up with an idea that, in a piece like “Ife”, for example, the relationship between thirds, major and minor thirds—and that’s an intervallic kind of structure. Go to any of those pieces and you’ll find they have half-note relationships. Like if the melody, say the melody is six bars long and say it starts on a C, the next time they come back if there’s a rotation of somewhat similar material it’ll start on C sharp, and it’ll go to a much larger interval than it did before. And then eventually it will keep moving like that, and the top note will also be moving downward in chromatics, in a half-step relationship, and you end up seeing that these kinds of endeavors, musical endeavors, clearly meant that he saw his melodic units as material, or formula, for how you make a piece of music. I’m talking in terms of, you know, like a mathematical formula where you can engage it from various points of views and come up with various, different kinds of answers but the formula itself is not changing. I was wondering in relation to that, when you take something like Jack Johnson, which obviously at the end with the clip, he’s putting it in a very political, social context as well, how does that factor into both the analysis of the music for you and ultimately your take on it? That’s a very nice one because you see like all these incidents we talk about regarding the art object itself, it does not come in an isolated environment, it comes out of a person who is in a social sphere. And that social sphere, everything that concerns them is placed in not just one piece but in every piece. You see, because I truly believe that a socialized being expresses their notion about that society continuously, if they’re working in art, or if they’re working in a factory, or working as a teacher. These moments constantly barrage them in some kind of way for some kind of conclusion, you know, some kind of way of making it fit into the reality of how they see things. Jack Johnson is an overt political statement, but Filles de Kilimanjaro is also a very overt political statement. And it’s a political statement that reaches across the Atlantic, you see. I believe that one had something to do with the revolution taking place in Southern Africa. And when you look at, I’ve just got the score in front of me, when you look at that piece of music, the first melody starts on the note D, then goes for six bars with two bars of rest. And then starts on the note E, which is a whole-step up. Then it has five bars of melody and three bars of rest. And the next note is an E, which is a repetition of the starting note before, but it’s a different kind of passage, which is only three bars long, with again three bars of rest. The very next note starts a half-step up above E on the note F, you see. And then the next passage, which is a three-bar passage, and the next passage starts on a G, which is again another full-step up. And these things are consistently happening in his music when you look at how he evolved melody. And if we put those particular few bars together and begin to look at systematically how he’s alternating between a half-step and whole-step and the amount of volume and the amount of rests, all of them play significant factors in how he makes this formula work. And that’s one of the earlier pieces, that’s a piece that’s not so much, you know, crowded, like “ Calypso Frelimo”. That piece has multiple consequences of pan-tonal and pan-structural, and also multilayered... it starts at an intense level that no one could ever count off and start at. So it has something to do also in the context of understanding the language, to push it with electronic elements. That is, it started from a mix, you see, and it started at a level that could not have been achieved on downbeat. You see, that’s pretty way ahead, if you think about it. I had another question about the politics... OK, but you see what I’m trying to say is that the politics is always there, and I’m saying that these artists, though they may not be vocal and make manifestos and stuff like that, their music speaks clearly of that. I mean Tutu is also another political statement, an overt one. I’m actually doing research now on Max Roach, and so I’m dealing with the albums from ’58 to ’62... Ahhhhhh. Uh Huh. You dealing with Freedom Now Suite? Yeah. But what I wanted to focus on in particular is “Garvey’s Ghost”, because there are no lyrics to... Yeah, yeah. [Sings the first three measures of “Garvey’s Ghost”.] And so what I’m writing is that he’s using a 6/8-swing there, and then over the top of that he’s using a cowbell pattern that is essentially derivative of a samba pattern, so it’s sort of an Afro-Brazilian feel. And so my contention is that with titling it “Garvey’s Ghost” is that it’s an example of Roach’s Garveyism through this sonic sort of sounding practice of taking jazz and Afro-Brazilian rhythms together. You know, that is actually quite true. And also, you know, Marcus Garvey, before coming to America, he actually did quite a bit of work in the Caribbean and also South America. And so, to cover those kinds of elements into a musical composition is quite brilliant. It meant that he not only knows Garvey’s name but that he also knows about Garvey’s history. He uses those elements to give those properties to his music. And also Max Roach wrote lots of papers for magazines and different organizations and stuff like that. He was quite vocal... quite vocal and outspoken. I wanted to ask you quickly about your own writing. You had mention in Notes (8 Pieces) that all of us are responsible for improvisations. Could you say a little bit more about that? Basically what I was trying to say is that there are many kinds of improvisations. And that improvisation itself, like composition... a clear definition of it is that it consists of a linguistic base, it is linguistically based. And that, as a language, it not only changes with a new context and information but it also changes because of evolution itself. You know, the language itself changes underneath to express something different. And improvisation has often been thought of as a one, mono-dimensional thing, that it is simply defined as, you know, one can do, or make do what they can do. But that’s more expressing the notion of ad hoc and that has nothing to do with improvisation. Improvisation has something to do with being the oldest music on the planet. And all of the early participants in that notion, though later probably defining it limited it in some ways, have contributed to a historical base of it. But only in modern times has it really taken on the true notion of language and has been nourished by a community of people who see that kind of responsibility and participate in it, you know. I was speaking earlier to another guy about Europe, about the notion of improvisation in Europe, and I mentioned that with all this literary technology in Europe you would die to find any serious text written on improvisation before modern times... and always written after the fact as opposed to written by a community or culture that actually respected and used improvisation in the way we think about it today. That stuff just doesn’t exist. [part 1 / part 2] |