| |

FLASHBACK

#05

International Festival Musique Actuelle : Victoriaville 1992

by Frank Rubolino

photographs courtesy of Michel Levasseur Productions Plateforme, Inc.

April 2001

This was my second trip to Victoriaville, the small farming community

located about 100 miles northeast of Montreal. I was quite excited

about their 10th anniversary edition of this cutting-edge festival

held in a town that has opened its arms to lovers of the new music

with its warm and welcome atmosphere. I was also met with some apprehension

about its future, because the city fathers had questioned the economic

value of a festival that draws a select, knowledgeable but limited

crowd. The festival producers had already announced that the next

edition would not occur until 1994, and the timeframe would change

from fall to spring. As we know, it has remained and prospered in

Victoriaville to the delight of its many fans, so I need not have

worried.

I quickly forgot about these problems and settled in to enjoy full

immersion with 25 up-coming concerts. The performances rotated among

a beautiful Catholic church, a transformed social hall, and a smaller

auditorium. This change of venue after each set was welcome and necessary

to maintain one's stamina over the four and one-half day period. The

festival attracts a certain number of repeat devotees from as far

off as Orlando, Vancouver, San Francisco, Chicago and of course Houston,

and this year we heard performers from the USA, Canada, Great Britain,

Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, Holland, Belgium and France. Following

are comments on selected concerts:

Jean Derome and his Dangerous Zhoms opened this large festival with

a fluid performance. I was unable to tell the improvised parts from

the written music of this tight group, whose cohesive music flowed

in seamless fashion. The band was fortified by a heavy front line

of Derome, reed player Robert Lepage, and trombonist Tom Walsh, while

guitarist René Lussier artfully steered the action in varying directions.

Lussier also played an eerie instrument called the daxophone by bowing

its edges to produce weird tones. The group played three extended

pieces that went through multiple movements and mood changes, but

each contained a Caribbean rhythm segment driven by Guillaume Dostaler,

Pierre Cartier, and Pierre Tanguay. Given the free form of most of

the other sections, the rhythmic portions tended to hold the pieces

together. All compositions were by Derome, including one called "In

Short Trousers I Freeze", which he wrote impulsively while waiting

for a train. The free sections often exploded over a background of

rhythm, while the music went from atonal to structured sound regularly.

Walsh, who also fronts his own group, was a dominant force on his

instrument, and his stature and T-shirt stating "Steal Cars, Not Bikes"

added to this impression. Derome is an extremely accomplished instrumentalist

and composer. His group did a great job of conveying its talent while

getting the crowd warmed up for the lengthy festival.

The crowd relocated to the club with Bill Frisell leading a band made

up of super-individualists who capably fit into varied musical contexts.

I was a little skeptical as to how a guitarist could lead the horn

lineup of the stature of Don Byron, Curtis Fowlkes and Billy Drews,

but Frisell took command on the opening downbeat and never let up.

Frisell could pass for a college professor, given his thick eyeglasses

and studious look, but when he opened the set with a long free-form

solo while constantly fidgeting with several outboard electronic controls,

you knew that this perception was totally invalid. The horn section

took turns playing off Frisell's guitar motivation. Each piece featured

long solos and duets, but all tunes contained full ensemble playing.

Drummer Joey Baron appeared at times out of control with his wild

playing, and sticks flew from his direction over the stage regularly.

Fowlkes and bass player Kermit Driscoll established the low register,

while Byron on clarinet soared over, under and between them. Frisell's

fragmented guitar style boded well with the duet/ensemble approach

as he moved through marches, a klezmer piece, and humorous/serious

melodies. Byron switched between clarinet and bass clarinet to confirm

his premier status of the day. Fowlkes' trombone style is driving

and pushing, but he makes the big horn sing in his hands. Most pieces

started without structure but then fell into hummable refrains. This

group had appeal with its huge sound and earned an encore from a crowd

that did not want to let them go.

The crowd relocated to the club with Bill Frisell leading a band made

up of super-individualists who capably fit into varied musical contexts.

I was a little skeptical as to how a guitarist could lead the horn

lineup of the stature of Don Byron, Curtis Fowlkes and Billy Drews,

but Frisell took command on the opening downbeat and never let up.

Frisell could pass for a college professor, given his thick eyeglasses

and studious look, but when he opened the set with a long free-form

solo while constantly fidgeting with several outboard electronic controls,

you knew that this perception was totally invalid. The horn section

took turns playing off Frisell's guitar motivation. Each piece featured

long solos and duets, but all tunes contained full ensemble playing.

Drummer Joey Baron appeared at times out of control with his wild

playing, and sticks flew from his direction over the stage regularly.

Fowlkes and bass player Kermit Driscoll established the low register,

while Byron on clarinet soared over, under and between them. Frisell's

fragmented guitar style boded well with the duet/ensemble approach

as he moved through marches, a klezmer piece, and humorous/serious

melodies. Byron switched between clarinet and bass clarinet to confirm

his premier status of the day. Fowlkes' trombone style is driving

and pushing, but he makes the big horn sing in his hands. Most pieces

started without structure but then fell into hummable refrains. This

group had appeal with its huge sound and earned an encore from a crowd

that did not want to let them go.

After two acts of relatively large ensembles, Paul Plimley and Lisle

Ellis' conventional quartet of piano, bass, drums and horn was a

change. Any similarity between convention and this group is totally

inconceivable. This after-hours set started at 12:45 AM at the smaller

hall, which had great acoustics. Clad in multi-colored pantaloons

that set the tone for the adventuresome playing to come, Plimley

propelled the band through a totally fulfilling set. The opening

number took on the quality of chamber music and included very close

interplay. Gregg Bendian was surrounded by vibes that he played intermittently

between driving drum passages. The group playing often dealt with

pure sound, such as when Freedman played only on his mouthpiece,

Plimley strummed the piano wires, Bendian bowed the edge of the vibes

keys with his drumstick, or Ellis used the bow to make exotic sounds

jump from his bass. They then moved into a hard-driving piece featuring

Bruce Freedman, who took his alto on a long, layered sound excursion.

Plimley was a master at building tension and then releasing it. Ellis's

playing was truly remarkable in its beauty, intensity, and energy. "It's A

Jig", written by Freedman, started in just that context and led into

some phenomenal blowing that made me forget it was 2 AM. The piece

ended a draining set for both the players and the audience.

Day two began at the smaller hall with again a larger group—both

in size and in sound. Featuring François Houle on soprano and clarinet

and surrounded by the heavy sounds of a tuba, trombone and alto, he

and his Et Cetera band assaulted the audience with their force. The

set consisted of three pieces, two of which went 30 minutes each.

The first number started with a guitar solo but quickly moved through

the horn sections from alto to soprano to trombone and tuba. Brad

Muirhead's trombone playing was extremely strong. The compositions

paid homage to Monk, John Carter and Albert Ayler. The moods shifted

frequently but were always anchored by the heaviness of the trombone

and tuba. Included in one piece was a passage from the traditional

"Abide With Me" that offered a brief quiet moment before it moved

into an intense improvisational phase. Ian McIntosh played a tuba

solo on one song that demonstrated his circular breathing technique,

and he also played the droning didgeridou. This established the backdrop

for Houle, who removed the bottom section from his clarinet to emit

an Indian flute sound. It was a moody piece in parts, and Houle also

used circular breathing. On piano, Houle was more the conductor as

he spurred Tanguay and Cartier. The set ended with a huge ensemble

sound. It was a great wake-up call to start the second day of the

festival.

Day two began at the smaller hall with again a larger group—both

in size and in sound. Featuring François Houle on soprano and clarinet

and surrounded by the heavy sounds of a tuba, trombone and alto, he

and his Et Cetera band assaulted the audience with their force. The

set consisted of three pieces, two of which went 30 minutes each.

The first number started with a guitar solo but quickly moved through

the horn sections from alto to soprano to trombone and tuba. Brad

Muirhead's trombone playing was extremely strong. The compositions

paid homage to Monk, John Carter and Albert Ayler. The moods shifted

frequently but were always anchored by the heaviness of the trombone

and tuba. Included in one piece was a passage from the traditional

"Abide With Me" that offered a brief quiet moment before it moved

into an intense improvisational phase. Ian McIntosh played a tuba

solo on one song that demonstrated his circular breathing technique,

and he also played the droning didgeridou. This established the backdrop

for Houle, who removed the bottom section from his clarinet to emit

an Indian flute sound. It was a moody piece in parts, and Houle also

used circular breathing. On piano, Houle was more the conductor as

he spurred Tanguay and Cartier. The set ended with a huge ensemble

sound. It was a great wake-up call to start the second day of the

festival.

What a stunning concert the Konrad Bauer Trio was. The acoustics

of the church were perfect for this trio of superstars. They opened

with total group improvisation with Günter Sommer being the driving force

on drums. He listened intently to the others and fully complemented

them without being competitive. Peter Kowald worked magic on the bass,

using both his strumming technique and his bow. At one point, he did

both. With the bow lodged under the strings, he was able to choose

or do both simultaneously. Konrad Bauer's tone is extremely smooth,

and he exhibited sustained energy that flowed even though the playing

was freeform. The group's communicative skills were intense. The second

piece found Bauer acting as a rock-solid force. Interspersed during

the evening were solo presentations. Kowald displayed great dexterity

using his knuckles rather than his fingers while spewing out mouthed,

guttural moans. The drum solo was entertaining as well as moving.

Using comic relief, Sommer pranced around his kit, splashing feathers

into the air or letting his fingers dance over the cymbals. The final

piece featured heavy dynamics as the group responded to the audience's

appreciation. After his solo concert last year, Bauer had become a

favorite at Victoriaville, and the love and respect he was shown was

immediately evident.

Talk about having fun, Fred Frith's Stone, Brick, Glass, Wood, Wire

band really did. The big band was a startling switch from the previous

trio. Their performance contained all the earthy elements defined

in its title. As conductor, Frith used a series of colored charts

instead of written music to proceed through what he termed 'playing

his photographs'. Seeing a harp, electric harp, and accordion mixed

in with electronic and conventional instruments gave no clue of what

was coming. What did come was a bold, dynamic sound from musicians

who responded beautifully to Frith's direction. The playing was intense,

and on the opening number, each soloist had the option to pick the

next player. You saw hands pointing regularly to the randomly chosen

next soloist. Lussier again appeared with his daxophone, and this

time he created a different mood with bowed screeching. During the

spontaneous playing, I detected sequences from Italian, French and

Oriental themes. Frith was able to evoke a sense of total cacophony

and then was able to turn it off instantly—only to start burning

again at the flick of his wrist. He also played an electrical stringboard

that he sawed, hammered or strummed at will. Han Bennink's power as

a drummer was overwhelming. He is a big man in stature, but his drum

sound is even larger. The force and motivation he produced could be

felt by everyone in the packed club. No one soloed at length, but

then again, everyone soloed continually. I was most impressed with

Zeena Parkins' harp playing, which was wild yet controlled. Myra Melford

did get some longer playing time, while totally free blowing swirled

in and out. Frith's leadership reminded me of the term 'conduction',

which Butch Morris uses to describe his directorship. This was a power

set, and having heard two premiere drummers of the caliber of Sommer

and Bennink back-to-back was awesome.

For Barre Phillips/Alain Joule's Brick On Brick, the visual imagery

of the stage was intriguing to the audience as it walked in. Joule's

percussion set was a cage that surrounded him with drums, bells,

chimes, gongs, pots, cymbals and numerous other items hanging from

bamboo poles. This would prove to be the perfect foil for Phillips'

impeccable bass style. Joule used various thick sticks, clappers,

and morocco to get multiple sound effects out of all of his toys,

and this was communicated directly to Phillips. The two others were

in the rear of the room interspersing pre-recorded bass or percussion

sounds taken from previously played segments. This had the effect

of filling in the sound in layers. Phillips played a beautiful, totally

bowed bass solo with cello-like sonority. Joule then used his cymbals

by scratching them with the stick ends to match the high notes from

the bass or by manipulating two or three striking objects in his

hands simultaneously for a denser response. He also employed a necklace-style

string of little cymbals. On one piece, Joule did a lengthy percussion

solo over a pre-recorded bass part, and then Phillips took up the

play while the recording featured Joule. They both eventually came

together in real-time. The audience, as at all concerts, was highly

attentive and did not ever interrupt the music with inappropriate

applause. This was a very intense show propelled by the dexterity

and diversity of Phillips and Joule.

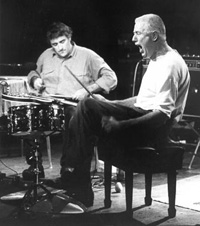

I was not sure what to expect from the pairing of Fred Frith and Han

Bennink. A European super-drummer who has played in the avant-garde

style for a number of years matched with a younger guitarist whose

music makes heavy use of electronics. Well, it opened with a bang

and kept that same pace throughout. Bennink entered, stooping his

tall frame to drum on the floor to get the rhythm started before he

sat down. Frith used a bow on his electric guitar in a percussive

beat to the cadence set by Bennink. He also used a paintbrush to strike

the strings, so the two were virtually in competition as percussionists.

Bennink made use of every drum and cymbal in his kit and exhibited

his well-known showmanship. At one point, he cut paper to get a clicking

sound from scissors, and then he put the clippings between two cymbals

and lit a fire to produce a smoke screen amidst a barrage of drumming

activity. This all was done to the accompaniment of Frith's electronics.

Bennink threw cymbals on the floor and drummed them and then tossed

one into the aisle a few feet from me. He jumped offstage and proceeded

to keep the beat by hitting the cymbal on the floor. Bennink would

spin cymbals, and the stone-quiet room was filled with the rotating

whirl until the cymbals collapsed. Both musicians were the drivers

of this performance. The audience could not get enough of this duo

and forced the first double encore of the festival.

I was not sure what to expect from the pairing of Fred Frith and Han

Bennink. A European super-drummer who has played in the avant-garde

style for a number of years matched with a younger guitarist whose

music makes heavy use of electronics. Well, it opened with a bang

and kept that same pace throughout. Bennink entered, stooping his

tall frame to drum on the floor to get the rhythm started before he

sat down. Frith used a bow on his electric guitar in a percussive

beat to the cadence set by Bennink. He also used a paintbrush to strike

the strings, so the two were virtually in competition as percussionists.

Bennink made use of every drum and cymbal in his kit and exhibited

his well-known showmanship. At one point, he cut paper to get a clicking

sound from scissors, and then he put the clippings between two cymbals

and lit a fire to produce a smoke screen amidst a barrage of drumming

activity. This all was done to the accompaniment of Frith's electronics.

Bennink threw cymbals on the floor and drummed them and then tossed

one into the aisle a few feet from me. He jumped offstage and proceeded

to keep the beat by hitting the cymbal on the floor. Bennink would

spin cymbals, and the stone-quiet room was filled with the rotating

whirl until the cymbals collapsed. Both musicians were the drivers

of this performance. The audience could not get enough of this duo

and forced the first double encore of the festival.

Every festival has its highlight, but for the second time Marilyn

Crispell was part of that highlight for me at Victoriaville. This

year she was featured with Anthony Braxton's quartet. Braxton is a

beautiful composer and impeccable multi-instrumentalist. Together

with Mark Dresser and Gerry Hemingway, the band presented an 80-minute

Braxton original that awed the crowd. Braxton deftly switched from

alto, sopranino, clarinet, flute and contra-bass clarinet showing

dexterity and sensitivity as he guided the group through one of his

typically difficult, multi-movement compositions. When Crispell took

her solos, she thoroughly captivated an audience seen rocking in the

church pews in a closed-eye trance. Her dynamics took hold of everyone

as Braxton gave her space to explore the piece. She did more than

explore it—she totally engulfed it. Hemingway combined his near-perfect

drumming with some astute vibe playing that added another dimension

to the quartet. Dresser was a solid contributor on bass, yielding

a bold sound that held the piece together. When Braxton played his

contra-bass clarinet, he seemed to be competing with Dresser's bass

line. The entire composition was a series of tension building and

releasing created mainly by Braxton's instrument switching or by Crispell's

prodding. Braxton seemed to prefer the sopranino tonight (his alto

needed some on-stage repairing at the concert's start), but the alto

was the instrument of choice to end the piece with a lengthy, consuming

solo that matched the frenzied mood he had set. He soared on the horn

with high energy without any accompaniment and then abruptly stopped.

The crowd jumped to its feet in applause. Braxton did not bother to

leave the stage. He simply whispered to the group, and they broke

out in a rendition of Coltrane's "Impressions". It was a concert of

great strength, and the many years Braxton has been associated with

the others was fully evident.

Every festival has its highlight, but for the second time Marilyn

Crispell was part of that highlight for me at Victoriaville. This

year she was featured with Anthony Braxton's quartet. Braxton is a

beautiful composer and impeccable multi-instrumentalist. Together

with Mark Dresser and Gerry Hemingway, the band presented an 80-minute

Braxton original that awed the crowd. Braxton deftly switched from

alto, sopranino, clarinet, flute and contra-bass clarinet showing

dexterity and sensitivity as he guided the group through one of his

typically difficult, multi-movement compositions. When Crispell took

her solos, she thoroughly captivated an audience seen rocking in the

church pews in a closed-eye trance. Her dynamics took hold of everyone

as Braxton gave her space to explore the piece. She did more than

explore it—she totally engulfed it. Hemingway combined his near-perfect

drumming with some astute vibe playing that added another dimension

to the quartet. Dresser was a solid contributor on bass, yielding

a bold sound that held the piece together. When Braxton played his

contra-bass clarinet, he seemed to be competing with Dresser's bass

line. The entire composition was a series of tension building and

releasing created mainly by Braxton's instrument switching or by Crispell's

prodding. Braxton seemed to prefer the sopranino tonight (his alto

needed some on-stage repairing at the concert's start), but the alto

was the instrument of choice to end the piece with a lengthy, consuming

solo that matched the frenzied mood he had set. He soared on the horn

with high energy without any accompaniment and then abruptly stopped.

The crowd jumped to its feet in applause. Braxton did not bother to

leave the stage. He simply whispered to the group, and they broke

out in a rendition of Coltrane's "Impressions". It was a concert of

great strength, and the many years Braxton has been associated with

the others was fully evident.

The London Jazz Composer's Orchestra is a dedicated experiment. Being

able to mold and control the egos of so many European individualists

is a feat unto itself, but Barry Guy, as leader of this auspicious

group, has achieved just that. He obviously understands their needs,

and the two long pieces that constituted the first of two concerts

gave all of them space to express themselves. On the opening "Double

Trouble", most of the trumpet section had their turn relatively early.

This was not just a 'stand up and blow' opportunity. The composition

was very tightly written so that the ensemble entered at various points

during a solo to add shading, coloring, or vitality to the playing.

The music featured two bass players—Guy and the articulate Barre

Phillips, and together they were a true force. Particularly strong

tenor work came from Evan Parker, who blew in his recognizable dissident

style. Trevor Watts' tenor was quite different but still very challenging.

Guy switched the soloists within sections to maintain diversity, adding

a trombone part, then a piano, then violin, etc. Guy also introduced

some interesting pairings. First Pete McPhail and Steve Picard played

in duet, then Watts with tuba player Steve Wick. Although all individual

offerings were memorable, the composition and arrangement were really

the stars. The second tune "Polyhymnia" opened with a bowed bass duo,

followed by a Watts solo that set a pattern for much longer individual

efforts than heard in the opener. Guy again used a series of duets,

such as a violin/trumpet or piano/trumpet match, and he continued

to interject the ensemble into appropriate spots. Only Paul Lytton

on drums did not get a spotlight, but then again, he was on for the

entire presentation as he drove both pieces. The audience was aware

that we would be treated to another concert tomorrow and wisely did

not demand an encore.

Having a band back for a second day is not routine for Victoriaville,

but the LJCO could not be fully absorbed in just one sitting. The

entire ensemble was again on stage in force. The opening "Study" was

a brooding tune that featured both bass players at the start in a

captivating duet that came off beautifully. In contrast to the previous

night's performance, no other solos followed. Instead, we were treated

to a moody tune that flowed as an ongoing wave without being overwhelming

in volume. The ensemble work was impeccable. The meditative piece

lasted 30 minutes and had sustained tension. But Guy saved the group's

best effort until last. He presented his "Harmos" to put the audience

in a daze. It started with a hummable refrain but proceeded to build

incredible dynamics. Using all of the forces at his disposal, Guy

created a sense of fierceness that resulted in the greatest big band

offering I had ever witnessed. Using solo or duet groupings with ensemble

coloring, he created a masterful moment. Of particular force was a

Guy/Lytton/Parker trio section. Guy worked the band to perfection,

creating shades and nuances and then total cacophony—only to

revert to softer passages. As the final soloist, Parker spoke for

the entire band on his horn as he burned an incredibly strong offering.

Every contributor was outstanding, and it emanated from the momentum

built up by the preceding player. The high ensemble ending brought

the audience to its feet, and although the applause was thunderous,

no one really expected an encore. Nothing could top what we had just

heard.

This next concert almost did not happen. In route from New York by

car the previous day, Fred Hopkins and Diedre Murray were involved

in a car accident that left them bruised and in slight shock. The

promoters arranged to fly them to the festival just before the scheduled

starting time. The crowd showed its appreciation for their 'show must

go on' attitude as soon as they walked on stage. You might think a

bass/cello duet would not be exciting or would have trouble filling

an entire set. You would have to reverse your thoughts after hearing

them. Murray's cello playing is lyrical and melodic, and she showed

extensive talent for communicating with Hopkins. At times, Murray

and Hopkins were both bowing their instruments, but the most gorgeous

sound came when Hopkins picked and strummed and Murray bowed. The

tunes at times were mystical, especially the haunting melody "Never

To Return", which Murray wrote in memory of her brother who had died

exactly one year ago. This was heavy stuff. Murray's range on cello

was far-reaching and her command over her instrument was obvious from

the start. Hopkins was visibly in pain from the accident, as evidenced

by his facial grimacing, but he never let it interfere with his playing.

The audience should have been more understanding to their physical

plight, but they stomped their feet at the end and demanded an encore.

The players were so moved by the audience's response that they came

back and did a sensitive reading of Ellington's "In A Sentimental

Mood". Their playing was filled with passion and feeling. I was thankful

for innovative musicians such as these who were willing to take risks

and be other than conventional. Immediately after the concert, Victo

Records premiered the recent studio date of this amazing duo. I was

most pleased to see "Never To Return" on it and naturally bought it

immediately.

This next concert almost did not happen. In route from New York by

car the previous day, Fred Hopkins and Diedre Murray were involved

in a car accident that left them bruised and in slight shock. The

promoters arranged to fly them to the festival just before the scheduled

starting time. The crowd showed its appreciation for their 'show must

go on' attitude as soon as they walked on stage. You might think a

bass/cello duet would not be exciting or would have trouble filling

an entire set. You would have to reverse your thoughts after hearing

them. Murray's cello playing is lyrical and melodic, and she showed

extensive talent for communicating with Hopkins. At times, Murray

and Hopkins were both bowing their instruments, but the most gorgeous

sound came when Hopkins picked and strummed and Murray bowed. The

tunes at times were mystical, especially the haunting melody "Never

To Return", which Murray wrote in memory of her brother who had died

exactly one year ago. This was heavy stuff. Murray's range on cello

was far-reaching and her command over her instrument was obvious from

the start. Hopkins was visibly in pain from the accident, as evidenced

by his facial grimacing, but he never let it interfere with his playing.

The audience should have been more understanding to their physical

plight, but they stomped their feet at the end and demanded an encore.

The players were so moved by the audience's response that they came

back and did a sensitive reading of Ellington's "In A Sentimental

Mood". Their playing was filled with passion and feeling. I was thankful

for innovative musicians such as these who were willing to take risks

and be other than conventional. Immediately after the concert, Victo

Records premiered the recent studio date of this amazing duo. I was

most pleased to see "Never To Return" on it and naturally bought it

immediately.

Maarten Altena's presence was very much anticipated by me because

I had read so much about this Dutch bass player. At the church, he

played with a very large contingent of musicians who had sponsorship

from the Dutch Cultural Foundation and other government agencies.

The Ensemble's tenor, flute, violin, and trombone players on the

left side of the stage were particularly appealing. Nevertheless,

the overall performance was somewhat of a disappointment. The music

of Altena is cerebral and cold and has no basis in the blues or African/American

music. As the star, Altena displayed no exceptional instrumental

talent and abdicated the conducting role by letting others in the

group give the directional signals. Vocalist Jannie Pranger was a

major part of the presentation, and her range and crystal-clear tone

were extremely good. She interjected high-pitched sounds in emulating

an instrument, but overall, the pieces did not have cohesiveness.

Drummer Michael Vatcher's role was in keeping with the detached feeling

of futuristic sounds of the 21st century. One piece called "Maal" did have some

sustained drive, but it also maintained a European feeling of lack

of soul. Given all the fanfare Altena had received to-date, I had

to wonder if my ears were missing something. Several others echoed

my sentiments of a sterile music that was devoid of feeling.

Elliott Sharp presented two back-to-back concerts using very different

lineups. This first group consisted primarily of strings, included

Sharp on guitar, two violinists, cellists, a violist, and a bassist.

Sharp resembled an escapee from Star Trek with his shaved head,

and his music and antics were fit for outer space as well. He manipulated

a double-necked guitar played at ear-piercing volume, and his long

composition could be described as serious noise. The stringed instruments

were played at breakneck speed and fortunately came back regularly

to a recognizable pattern of sound that had drive and excitement.

The piece was compositionally akin to the work of Günter Schuller.

The players worked from cues by Sharp but mostly were involved in

group improvisation. Seldom did any player other than Sharp solo,

and his were screeching affairs. From sheer motivational effort and

volume, this was the most far-afield show so far. It was a continuous

performance of variations on a constant theme and became increasingly

engrossing. I liked it.

Sharp's second concert at the same club was more of an electronic

affair. Substituting the electric harp of Parkins and the synthesizer

of Mark Degliantoni for the string ensemble, he gave an even wilder

show. At times the sound was nothing but a blur, and you simply had

to let it wash over you rather than try to interpret or dissect it.

Zeena Parkins, who comes from a family of professional musicians,

was a marvel on harp. Her vibrancy and animation were fun to watch.

The bass tone on this show was the lowest I have ever heard. Whether

it came from the speakers or the instruments, you could actually feel

a sensation from the throat to the intestines. It was an internal

feeling that traveled straight through your body. I am sure a pacemaker

would have been totally destroyed by this show. Sharp also used his

voice to get a guttural sound that emulated the bass tones. He held

his finger on his throat to produce a growling, intense resonance.

This performance showed just how far out the music can get.

What an exciting surprise my first encounter with Urs Leimgruber and

Fritz Hauser was. I had no idea what form of music these Swiss musicians

would present. Several of the press in the audience attempted to describe

it as dealing with space and sound. They could not have been more

inaccurate. Leimgruber played extended soprano and tenor improvisations

with sustained drive that was motivated by the intricate trap drumming

and percussion work of Hauser, whose playing was very delicate and

enhanced the ambiance of the totally silent room. The audience seemed

to be spellbound by the force of their hour-long set. On tenor, Leimgruber

displayed sheer energy, while on soprano, he soared. The total performance

was spontaneous, improvised and beautiful. Leimgruber often used the

circular breathing technique to project long lines of swirling, moving

sound. Hauser was the perfect foil and was engrossing to watch. He

is a big man in stature and dominates his instrument. On one solo,

he used a single cymbal and mallets to set a rhythm pattern that never

faltered. This crowd was definitely overwhelmed yet was astute enough

not to applaud at the end of the set until Leimgruber removed the

horn from his mouth. He held it there silently for 20 seconds before

he relaxed. The beauty of Victoriaville is that you can see talent

such as this that may have previously escaped you. I immediately ordered

their Hat Art duo album.

What an exciting surprise my first encounter with Urs Leimgruber and

Fritz Hauser was. I had no idea what form of music these Swiss musicians

would present. Several of the press in the audience attempted to describe

it as dealing with space and sound. They could not have been more

inaccurate. Leimgruber played extended soprano and tenor improvisations

with sustained drive that was motivated by the intricate trap drumming

and percussion work of Hauser, whose playing was very delicate and

enhanced the ambiance of the totally silent room. The audience seemed

to be spellbound by the force of their hour-long set. On tenor, Leimgruber

displayed sheer energy, while on soprano, he soared. The total performance

was spontaneous, improvised and beautiful. Leimgruber often used the

circular breathing technique to project long lines of swirling, moving

sound. Hauser was the perfect foil and was engrossing to watch. He

is a big man in stature and dominates his instrument. On one solo,

he used a single cymbal and mallets to set a rhythm pattern that never

faltered. This crowd was definitely overwhelmed yet was astute enough

not to applaud at the end of the set until Leimgruber removed the

horn from his mouth. He held it there silently for 20 seconds before

he relaxed. The beauty of Victoriaville is that you can see talent

such as this that may have previously escaped you. I immediately ordered

their Hat Art duo album.

Other acts at the festival included Arraymusic from Canada, Sovetskoe

Foto from Germany, X-Legged Sally from Belgium, Last Poets from the

USA, 5th Species from Canada, Abel-Steinberg-Winant trio from the

USA, Lar Hollmer Looping Home Orchestra from Sweden, Pierre Cartier

Chansons de Douve from Canada, and the Arto Lindsay band from the

USA. The day after the festival was a strange one. My body and mind

were geared to hear six more concerts, and I had to fight the depression

of not being able to experience more.

|

|

|

|

|